Coccidioidomycosis

Heather Largura DDS, MS, Janelle Renschler DVM, PhD, Joe Wheat MD

See Sykes, J.E. for more detailed information [1

Background

- Causative agents: Dimorphic fungi Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii.

- Route of infection: inhalation of spores, rarely cutaneous inoculation.

- At risk: large breed young adult dogs, although dogs of any breed, age, or gender affected [2

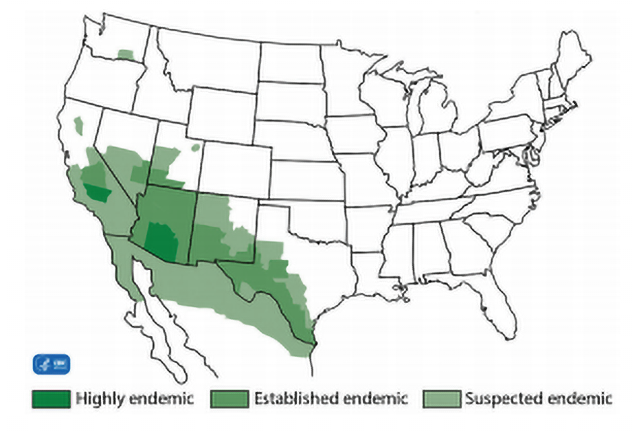

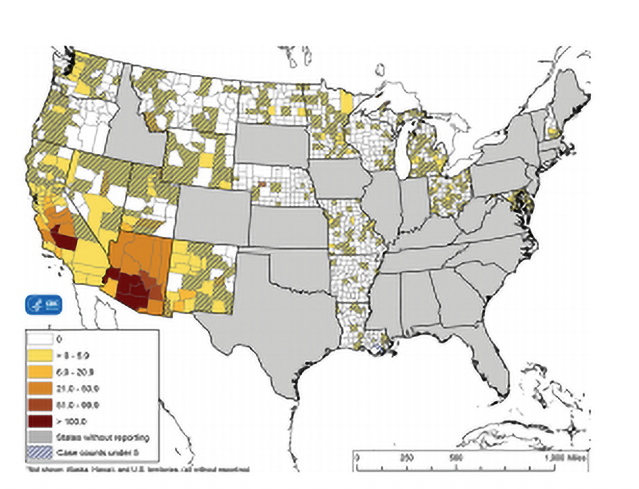

Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. , 3Maddy, K.T., Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1958. 132(11): p. 483-489. ]. Risk factors for dogs from AZ are being housed outdoors, roaming areas more than 1 acre, and walking in the desert [4Butkiewicz, C.D., L.E. Shubitz, and S.M. Dial, Risk factors associated with Coccidioides infection in dogs. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 2005. 226(11): p. 1851-1854. ]. Coccidioidomycosis occurs less frequently in cats; a recent study demonstrated a high percentage of cats (66%) with coccidioidomycosis had indoor only lifestyle [5Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ]. Exposure to spores can occur through open doors, windows, air conditioners, or fomites that enter the residence. - Endemic distribution: southwestern United States (California, Arizona, Utah, Texas, Nevada, New Mexico), Mexico, Central and South America. Endemic maps demonstrate evidence of coccidioidomycosis in new areas such as the state of Washington and Oregon [7

Marsden-Haug, N., et al., Coccidioidomycosis Acquired in Washington State. Clin. Infect. Dis, 2013. , 8Lockhart, S.R., O.Z. McCotter, and T.M. Chiller, Emerging Fungal Infections in the Pacific Northwest: The Unrecognized Burden and Geographic Range of Cryptococcus gattii and Coccidioides immitis. Microbiol Spectr, 2016. 4(3). ].

Areas Endemic for Coccidioidomycosis

Clinical Findings in Dogs: most infections are subclinical ~70% [9Shubitz, L.E., et al., Incidence of coccidioides infection among dogs residing in a region in which the organism is endemic. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 2005. 226(11): p. 1846-1850. Davidson, A.P., et al., Selected Clinical Features of Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs. Med Mycol, 2019. 57(Supplement_1): p. S67-S75. , 10Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]

Pulmonary: most common form of coccidioidomycosis, and often accompanied by disseminated findings.

- Signs: tachypnea, cough, dyspnea, exercise intolerance, lethargy, weight loss, anorexia [2

Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. , 10Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]. Cough can be associated with gagging or retching [1Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. ]. - Imaging: unremarkable, most common finding is slight to extensive hilar lymphadenomegaly, sometimes with interstitial pulmonary infiltrates, nodular interstitial, interstitial-alveolar, broncho-interstitial infiltrates and/or sternal lymphadenomegaly [2

Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. ].

Disseminated (extrapulmonary): 25%, may be accompanied by pulmonary involvement [2

- General/systemic:

- Nonspecific signs: Fever, lethargy, inappetence, and weight loss, diffuse muscle atrophy [3

Maddy, K.T., Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1958. 132(11): p. 483-489. , 11Angell, J.A., et al., Ocular coccidioidomycosis in a cat. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1985. 187(2): p. 167-169. ]

- Nonspecific signs: Fever, lethargy, inappetence, and weight loss, diffuse muscle atrophy [3

- Cutaneous lesions

- Signs: ulcerations with drainage, granulomas, subcutaneous abscesses, may overlie osteomyelitis [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 3Maddy, K.T., Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1958. 132(11): p. 483-489. ]

- Signs: ulcerations with drainage, granulomas, subcutaneous abscesses, may overlie osteomyelitis [1

- Peripheral Lymphadenomegaly

- Ocular involvement:

- Signs: uveitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, retinal detachment, and endophthalmitis [2

Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. , 12Shively, J.N. and C.E. Whiteman, Ocular lesions in disseminated coccidioidomycosis in 2 dogs. Pathol Vet, 1970. 7(1): p. 1-6. , 13Burtch, M., Granulomatous meningitis caused by Coccidioides immitis in a dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1998. 212(6): p. 827-829. ]

- Signs: uveitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, retinal detachment, and endophthalmitis [2

- Bone lesions: most common site of dissemination in dogs [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 10Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]- Signs: lameness, firm swellings, swollen joints, draining lesions, sinus tracts

- Imaging: osteolytic lesions with periosteal proliferation, can resemble osteosarcomas [3

Maddy, K.T., Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1958. 132(11): p. 483-489. , 5Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. ]

- CNS involvement:

- Signs: Seizures are most common [10

Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]. Additional signs are obtundation, blindness,

nystagmus, absent menace reflexes, diminished gag response, ataxia, abnormal placing reactions, pacing, circling, cervical pain, tetraparesis, [2Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. , 10Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. , 14Pryor, W.H., Jr., et al., Coccidioides immitis encephalitis in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 1972. 161(10): p. 1108-12. , 15Tofflemire, K. and C. Betbeze, Three cases of feline ocular coccidioidomycosis: presentation, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Vet. Ophthalmol, 2010. 13(3): p. 166-172. ]. - Imaging: Plain radiography is not diagnostic for lesions of brain or spinal cord. [10

Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]. Advanced imaging is primary means of differentiating CNS coccidioidomycosis from other neurological diseases, but definitive diagnosis cannot be made on MRI alone [10Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]. Half of CNS cases have meningoencephalitis [10Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ], brain lesions, ependymitis.

- Signs: Seizures are most common [10

- Other: cardiac, gastrointestinal, kidneys, bladder, testes, prostate, liver, spleen, GI tract, urinary tract

Clinical findings in cats

Pulmonary

- Signs: tachypnea 25-40% [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ] - Imaging: broncial, interstitial and/or alveolar pattern or consolidation of one or more lung lobes 41% [6

Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ], hilar lymphadenopathy 27% [5Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ], solitary lung masses or nodules 18% [6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ], and pleural effusion 24% [6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ].

Disseminated (extrapulmonary): 60% present with disseminated infection, perhaps due to delay in seeking care or recognition of infection [6

- General/Systemic: Fever present in 31-50% [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ], inappetence 52% [6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ] - Cutaneous lesions: present in 50-56%, draining skin lesions, subcutaneous granulomas, abscesses [5

Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ]. Coccidioidomycosis should be considered in cats from endemic region that present with chronic dermal lesions not responsive to empirical treatment [5Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ]. - Bone lesions lameness in 20-50% [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ]- Imaging: periosteal proliferation, osteolysis, soft tissue swelling; can resemble osteosarcoma [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 3Maddy, K.T., Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1958. 132(11): p. 483-489. , 5Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. ]

- Imaging: periosteal proliferation, osteolysis, soft tissue swelling; can resemble osteosarcoma [1

- Ocular involvement:13%; conjunctival masses, periorbital swelling, chorioretinitis, retinal detachment, endopthalmitis, anterior uveitis [12

Shively, J.N. and C.E. Whiteman, Ocular lesions in disseminated coccidioidomycosis in 2 dogs. Pathol Vet, 1970. 7(1): p. 1-6. , 16Gaidici, A. and M.A. Saubolle, Transmission of coccidioidomycosis to a human via a cat bite. J Clin Microbiol, 2009. 47(2): p. 505-6. ]. - CNS involvement: hyperesthesia, posterior paresis, seizures, ataxia [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. ]. - Other: abdominal organs such as spleen [17

Shubitz, L.F. and S.M. Dial, Coccidioidomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Clin. Tech. Small Anim Pract, 2005. 20(4): p. 220-226. ].

Laboratory abnormalities

- CBC: normocytic, normochromic nonregenerative anemia, mild leukocytosis from neutrophilia, monocytosis; lymphopenia.

- Serum chemistry profile: mild to moderate hyperglobulinemia (50%) [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. ], hypoalbuminemia, uncommonly mild hypercalcemia; increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP )with bony involvement [1Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 2Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. , 18Simoes, D.M., et al., Retrospective analysis of cutaneous lesions in 23 canine and 17 feline cases of coccidiodomycosis seen in Arizona, USA (2009-2015). Vet Dermatol, 2016. 27(5): p. 346-e87. ]. Cats may have no abnormalities (20%), neutrophilia with or without monocytosis with normal serum chemistries (33%), or hyperglobulinemia (43%) [6Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910. ]. - Urinalysis: occasional proteinuria.

- CSF analysis: increased total nucleated cell counts, increased CSF protein and reduced glucose concentration.

Diagnosis

Histology and cytology:

- Advantage: FNA or biopsy easy to perform if cutaneous lesions or lymphadenopathy present

and most rapid method for diagnosis. Dermatologic dissemination is frequent in cats, allowing for ease of obtaining sample [5Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. , 19Wolf, A.M., Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in a dog and a cat. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1979. 174(5): p. 504-506. , 20Holbrook, E.D., et al., Novel canine anti-Coccidioides immunoglobulin G enzyme immunoassay aids in diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis in dogs. Med Mycol, 2019. ]. - Disadvantage: risk and higher cost if more invasive procedure required in the absence of skin lesions or enlarged lymph nodes (i.e., respiratory specimens or surgical or ultrasound-guided biopsy).

Antigen detection:

- Advantage: easy to collect specimens, results available in a few days. Combined serum and urine antigen testing, AGID, and antibody EIA yields highest sensitivity (99%) [21

Kirsch, E.J., et al., Evaluation of Coccidioides antigen detection in dogs with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012. 19(3): p. 343-5. ]. - Disadvantage: low sensitivity: 20-34% [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. , 21Kirsch, E.J., et al., Evaluation of Coccidioides antigen detection in dogs with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012. 19(3): p. 343-5. , 22Graupmann-Kuzma, A., et al., Coccidioidomycosis in dogs and cats: a review. J Am Anim Hosp. Assoc, 2008. 44(5): p. 226-235. ] in dogs due to low fungal burden compared to other endemic mycoses, cross reactivity with histoplasmosis (7.7%) and blastomycosis (6.4%) [21Kirsch, E.J., et al., Evaluation of Coccidioides antigen detection in dogs with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012. 19(3): p. 343-5. ]. Sensitivity for antigen test was higher in cats in an unpublished study at MVD (100%; 7/7 cats with proven coccidioidomycosis based on organism ID).

Antibody Detection:

- Advantage: most sensitive method for diagnosis [23

LF, B.C.a.S. A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CANINE COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS CASES AT A TERTIARY CARE CENTER IN TUCSON. in 62nd Annual Coccidioidomycosis Study Group Meeting. 2018. Flagstaff, AZ. ].- MVista® Coccidioides Canine IgG Antibody Enzyme immunoassay (EIA): high sensitivity/specificity (89.2% / 97%) [21

Kirsch, E.J., et al., Evaluation of Coccidioides antigen detection in dogs with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012. 19(3): p. 343-5. ], results same day - Immunodiffusion (AGID): high sensitivity (90-92%) [2

Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466. , 21Kirsch, E.J., et al., Evaluation of Coccidioides antigen detection in dogs with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012. 19(3): p. 343-5. ], but 3 days to result and additional 3 day for titer. - Complement fixation test is positive in most cats with coccidioidomycosis [5

Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91. ]. It is not routinely used in dogs due to anticomplementary antibody presence [1Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. ].

- MVista® Coccidioides Canine IgG Antibody Enzyme immunoassay (EIA): high sensitivity/specificity (89.2% / 97%) [21

- Disadvantage: No commercially available feline-specific assay.

- Titer does not reflect severity of disease [9

Shubitz, L.E., et al., Incidence of coccidioides infection among dogs residing in a region in which the organism is endemic. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 2005. 226(11): p. 1846-1850. Davidson, A.P., et al., Selected Clinical Features of Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs. Med Mycol, 2019. 57(Supplement_1): p. S67-S75. , 24Crabtree, A.C., D.G. Keith, and H.L. Diamond, Relationship between radiographic hilar lymphadenopathy and serologic titers for Coccidioides sp. in dogs in an endemic region. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound, 2008. 49(6): p. 501-503. ] due to overlap in titer with clinical and subclinical disease [18Simoes, D.M., et al., Retrospective analysis of cutaneous lesions in 23 canine and 17 feline cases of coccidiodomycosis seen in Arizona, USA (2009-2015). Vet Dermatol, 2016. 27(5): p. 346-e87. ]. Negative serology does not rule out coccidioidomycosis [18Simoes, D.M., et al., Retrospective analysis of cutaneous lesions in 23 canine and 17 feline cases of coccidiodomycosis seen in Arizona, USA (2009-2015). Vet Dermatol, 2016. 27(5): p. 346-e87. , 25Pappagianis, D., Serologic studies in coccidioidomycosis. Semin. Respir. Infect, 2001. 16(4): p. 242-250. , 26Renschler, J.S., et al., Reduced susceptibility to fluconazole in a cat with histoplasmosis. JFMS Open Rep, 2017. 3(2): p. 2055116917743364. ]. Titers 1:8 may be found in 5-20% of healthy dogs.

- Titer does not reflect severity of disease [9

Culture:

- Advantage: only way to prove the diagnosis. Rarely performed.

- Disadvantages: Rarely performed in vet med. Some risk to laboratory personnel, so appropriate facilities are required. Cultures require 1 to 3 weeks incubation, up to 5 weeks occasionally; only used for basis of diagnosis in 12% of cases [9

Shubitz, L.E., et al., Incidence of coccidioides infection among dogs residing in a region in which the organism is endemic. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 2005. 226(11): p. 1846-1850. Davidson, A.P., et al., Selected Clinical Features of Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs. Med Mycol, 2019. 57(Supplement_1): p. S67-S75. ].

Molecular: inadequate information to determine usefulness

- Advantage: fast turnaround time, although no peer-reviewed publications available to assess sensitivity and specificity (making interpretation of the results difficult).

- Disadvantage: low incidence of fungemia so whole blood unlikely a desirable specimen, invasive procedure to obtain respiratory or tissue specimens, expensive.

Treatment

General

- Prognosis depends on severity of infection and extent of dissemination [1

Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915. ].- Initial hospitalization for intravenous amphotericin B and respiratory assistance may reduce mortality in severe cases.

- Outcome good to excellent in cases with CNS involvement that show resolution of clinical signs in first few weeks of treatment, but poor if deterioration or signs of static encephalopathy, or severe respiratory insufficiency [10

Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ].

Amphotericin B: 1 – 3mg/kg every other day, 3 times weekly. Deoxycholate or lipid formulation of amphotericin B are recommended as initial treatment for 3-7 days for cases with severe disease followed by itraconazole to complete therapy. Risk of nephrotoxicity.

Fluconazole: 10mg/kg q24h or 5mg/kg q12h. Fluconazole is the first drug of choice for coccidioidomycosis, with high bioavailability and low toxicity; however, resistance to fluconazole has developed in humans and cats with histoplasmosis [10

Itraconazole: 5mg/kg PO q 12 hours for 3 days (loading dose) then q 24 hours for dogs; higher doses may be required for cats.

- Uncomplicated cases: at least six to twelve months and resolution of signs, resolution or marked improvement of radiographic lesions and resolution of antigen [10

Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65. ]. - Complicated cases (bone, joints, CNS) or relapse despite appropriate therapy. At least 12 months and resolution of signs, radiographic lesions and antigen. In humans with CNS involvement, anti-fungal therapy is lifelong [28

Galgiani, J.N., et al., Comparison of oral fluconazole and itraconazole for progressive, nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis – A randomized, double-blind trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2000. 133(9): p. 676-686. ]. Human studies show Itraconazole more effective than fluconazole in treating skeletal infections [29Renschler, J., et al., Comparison of Compounded, Generic, and Innovator-Formulated Itraconazole in Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc, 2018. 54(4): p. 195-200. ]. - Use only FDA approved generic itraconazole or brand named Sporanox®. Compounded non-FDA approved preparations have poor bioavailability [30

Greene, R.T., Coccidioidomycosis, IN: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 1998, Philadelphia: WB Saunders. ]. The effectiveness of the non-FDA approved preparations for treatment of coccidioidomycosis is unknown. - Verify blood levels of itraconazole of at least 2 µg/mL after reaching steady-state (2 weeks in dogs

and 3 weeks in cats) is highly recommended [30Greene, R.T., Coccidioidomycosis, IN: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 1998, Philadelphia: WB Saunders. ].

Terbinafine: no published canine studies to support terbinafine, not recommended in humans. A rabbit model comparing terbinafine and fluconazole showed terbinafine to be ineffective in survival, histology and reduction in numbers of colony forming units 28

Ancillary therapy: glucocorticoids at anti-inflammatory doses for animals with respiratory distress or severe inflammation; however, for short duration [10

Surgical management: amputation for persistent osteomyelitis, pericardectomy in tamponade, and enucleation may be required for endopthalmitis [1

Monitoring response to treatment

Resolution of clinical signs and reduction in serological titers, though decision to terminate treatment should not be based on titer alone since titers may plateau or decrease slightly after recovery [23

Coccidioides antibody testing at 3-month intervals during and at 3, 6- and 12-months following discontinuation of treatment, until negative.

If Coccidioides antigen in serum or urine was initially positive, may be useful as a monitoring tool (treat until negative).

Imaging: resolution or marked improvement in radiographs, CT or MRI scans.

Antifungal susceptibility testing may be performed on cultured isolates. Services available at UT Health San Antonio Fungus Testing Lab.

Relapse: up to 25% of dogs relapse [23LF, B.C.a.S. A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CANINE COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS CASES AT A TERTIARY CARE CENTER IN TUCSON. in 62nd Annual Coccidioidomycosis Study Group Meeting. 2018. Flagstaff, AZ. ]

Diagnosis: recurrent signs and increase in antibody titer or antigen concentration.

Causes: use of non-FDA approved itraconazole, subtherapeutic levels of itraconazole, development of resistance to fluconazole and inadequate duration of treatment [30

Treatment

- Repeat itraconazole adhering to guidelines above.

- Chronic suppression with itraconazole 5mg/kg administered 3 times weekly may prevent relapse.

REFERENCES:

- Sykes, J.E., Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 2014, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 915.

- Johnson, L.R., et al., Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995-2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc, 2003. 222(4): p. 461-466.

- Maddy, K.T., Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1958. 132(11): p. 483-489.

- Butkiewicz, C.D., L.E. Shubitz, and S.M. Dial, Risk factors associated with Coccidioides infection in dogs. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 2005. 226(11): p. 1851-1854.

- Greene, R.T. and G.C. Troy, Coccidioidomycosis in 48 cats: a retrospective study (1984-1993). J Vet. Intern Med, 1995. 9(2): p. 86-91.

- Arbona, N., et al., Clinical features of cats diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2004-2018. J Feline Med Surg, 2019: p.1098612X19829910.

- Marsden-Haug, N., et al., Coccidioidomycosis Acquired in Washington State. Clin. Infect. Dis, 2013.

- Lockhart, S.R., O.Z. McCotter, and T.M. Chiller, Emerging Fungal Infections in the Pacific Northwest: The Unrecognized Burden and Geographic Range of Cryptococcus gattii and Coccidioides immitis. Microbiol Spectr, 2016. 4(3).

- Shubitz, L.E., et al., Incidence of coccidioides infection among dogs residing in a region in which the organism is endemic. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 2005. 226(11): p. 1846-1850.

Davidson, A.P., et al., Selected Clinical Features of Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs. Med Mycol, 2019. 57(Supplement_1): p. S67-S75. - Millman, T.M., Coccidioidomycosis in the dog: its radiographic diagnosis. J Am Vet Radiol Soc., 1979(20): p. 50-65.

- Angell, J.A., et al., Ocular coccidioidomycosis in a cat. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1985. 187(2): p. 167-169.

- Shively, J.N. and C.E. Whiteman, Ocular lesions in disseminated coccidioidomycosis in 2 dogs. Pathol Vet, 1970. 7(1): p. 1-6.

- Burtch, M., Granulomatous meningitis caused by Coccidioides immitis in a dog. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1998. 212(6): p. 827-829.

- Pryor, W.H., Jr., et al., Coccidioides immitis encephalitis in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 1972. 161(10): p. 1108-12.

- Tofflemire, K. and C. Betbeze, Three cases of feline ocular coccidioidomycosis: presentation, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Vet. Ophthalmol, 2010. 13(3): p. 166-172.

- Gaidici, A. and M.A. Saubolle, Transmission of coccidioidomycosis to a human via a cat bite. J Clin Microbiol, 2009. 47(2): p. 505-6.

- Shubitz, L.F. and S.M. Dial, Coccidioidomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Clin. Tech. Small Anim Pract, 2005. 20(4): p. 220-226.

- Simoes, D.M., et al., Retrospective analysis of cutaneous lesions in 23 canine and 17 feline cases of coccidiodomycosis seen in Arizona, USA (2009-2015). Vet Dermatol, 2016. 27(5): p. 346-e87.

- Wolf, A.M., Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in a dog and a catt. J Am Vet. Med Assoc, 1979. 174(5): p. 504-506.

- Holbrook, E.D., et al., Novel canine anti-Coccidioides immunoglobulin G enzyme immunoassay aids in diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis in dogs. Med Mycol, 2019.

- Kirsch, E.J., et al., Evaluation of Coccidioides antigen detection in dogs with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012. 19(3): p. 343-5.

- Graupmann-Kuzma, A., et al., Coccidioidomycosis in dogs and cats: a review. J Am Anim Hosp. Assoc, 2008. 44(5): p. 226-235.

- LF, B.C.a.S. A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CANINE COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS CASES AT A TERTIARY CARE CENTER IN TUCSON. in 62nd Annual Coccidioidomycosis Study Group Meeting. 2018. Flagstaff, AZ.

- Crabtree, A.C., D.G. Keith, and H.L. Diamond, Relationship between radiographic hilar lymphadenopathy and serologic titers for Coccidioides sp. in dogs in an endemic region. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound, 2008. 49(6): p. 501-503.

- Pappagianis, D., Serologic studies in coccidioidomycosis. Semin. Respir. Infect, 2001. 16(4): p. 242-250.

- Renschler, J.S., et al., Reduced susceptibility to fluconazole in a cat with histoplasmosis. JFMS Open Rep, 2017. 3(2): p. 2055116917743364.

- Sorensen, K.N., et al., Comparative efficacies of terbinafine and fluconazole in treatment of experimental coccidioidal meningitis in a rabbit model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother, 2000. 44(11): p. 3087-3091.

- Galgiani, J.N., et al., Comparison of oral fluconazole and itraconazole for progressive, nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis – A randomized, double-blind trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2000. 133(9): p. 676-686.

- Renschler, J., et al., Comparison of Compounded, Generic, and Innovator-Formulated Itraconazole in Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc, 2018. 54(4): p. 195-200.

- Greene, R.T., Coccidioidomycosis, IN: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 1998, Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

- Kriesel, J.D., et al., Persistent pulmonary infection with an azole-resistant Coccidioides species. Med Mycol, 2008: p. 1-4.

- Thompson, G.R., 3rd, B.M. Barker, and N.P. Wiederhold, LargeScale Evaluation of In Vitro Amphotericin B, Triazole, and Echinocandin Activity against Coccidioides Species from U.S. Institutions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017. 61(4).