Histoplasmosis in Veterinary Medicine 2020

INTRODUCTION

Histoplasmosis is a common enzootic mycosis in the United States. In a 1981 study, the case rates per 100,000 dog-years-at-risk at 14 colleges of veterinary medicine for histoplasmosis was 2.5 times higher than blastomycosis and 3.5 times higher than coccidioidomycosis [1Selby LA, Becker SV, Hayes HW, Jr. Epidemiologic risk factors associated with canine systemic mycoses. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:133-139.]. An older study showed that Histoplasma capsulatum was isolated from 22% of healthy appearing dogs from Cincinnati, Ohio while Blastomyces dermatitidis was isolated from only 2% [2Fattal AR, Schwarz J, Straub M. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from lymph nodes of spontaneously infected dogs. Am J Clin Pathol 1961;36:119-124.]. A second study showed that in Lexington, Kentucky, H. capsulatum was isolated from 40% of healthy dogs while B. dermatitidis was isolated from only 1% [3Turner C, Smith CD, Furcolow ML. Frequency of isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis from dogs in Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:137-141.]. Inexplicably, more recent clinical experience would suggest that isolation of H. capsulatum from dogs or cat without histoplasmosis is very uncommon. In Africa, histoplasmosis may be caused by H. capsulatum variety duboisii [4Gugnani HC. Histoplasmosis in Africa: a review. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2000;42:271-277.] and in Ethiopia and the Middle East by H. capsulatum variety farciminosum [5Gabal MA, Hassan FK, Siad AA, et al. Study of equine histoplasmosis farciminosi and characterization of Histoplasma farciminosum. Sabouraudia 1983;21:121-127., 6Ameni G. Epidemiology of equine histoplasmosis (epizootic lymphangitis) in carthorses in Ethiopia. Vet J 2006;172:160-165., 7Ameni G, Siyoum F. Study on Histoplasmosis (epizootic lymphangitis) in cart-horses in Ethiopia. J Vet Sci 2002;3:135-140.].

While histoplasmosis is not transmissible from animal to human, concurrent infection is not uncommon because of shared exposure [8Davies SF, Colbert RL. Concurrent human and canine histoplasmosis from cutting decayed wood. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:252-253.]. Histoplasmosis usually causes pulmonary or disseminated disease. Although likely a result of dissemination, disease apparently localized to a single body system including the skin, eye, bone/joints, and GI tract has also been reported [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 10Smith KM, Strom AR, Gilmour MA, et al. Utility of antigen testing for the diagnosis of ocular histoplasmosis in four cats: a case series and literature review. J Feline Med Surg 2017;19:1110-1118., 11Fielder SE, Meinkoth JH, Rizzi TE, et al. Feline histoplasmosis presenting with bone and joint involvement: clinical and diagnostic findings in 25 cats. J Feline Med Surg 2019;21:887-892., 12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073.]. Familiarity with these clinical manifestations may alert a veterinarian to consider the diagnosis. Antigen detection in urine and serum often provides a rapid diagnosis, precluding the need for invasive procedures to obtain specimens for organism identification or culture. Antibody testing may be useful in cases with negative antigen testing results. Itraconazole is the treatment of choice, and therapy should be monitored by antigen testing. Itraconazole absorption and metabolism vary considerably, at times causing undetectable or toxic blood levels, and blood level measurement (therapeutic drug monitoring) is encouraged to assure adequate drug exposure [13Renschler J, Albers A, Sinclair-Mackling H, et al. Comparison of Compounded, Generic, and Innovator-Formulated Itraconazole in Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018;54:195-200.].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

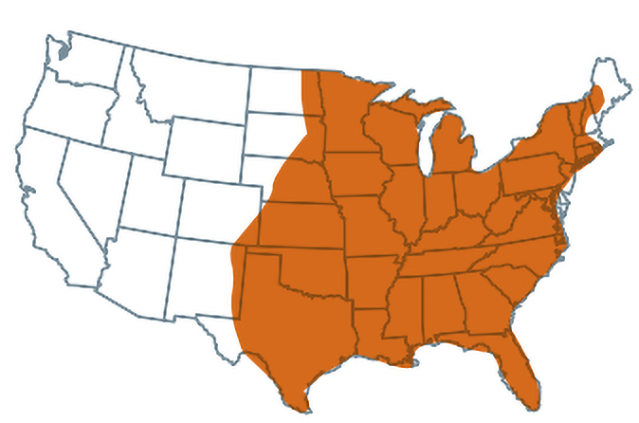

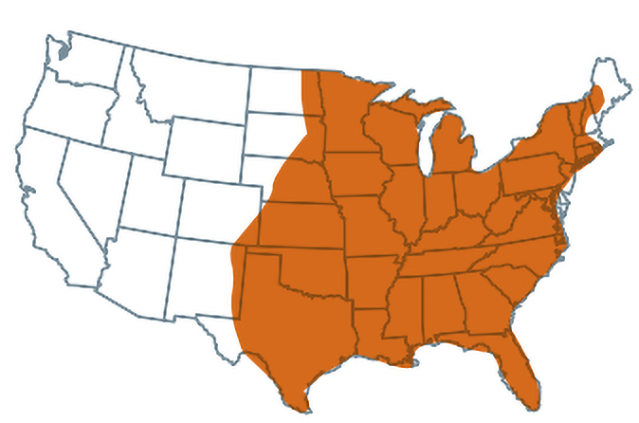

Histoplasmosis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum is enzootic in certain parts of North and South America. In the U.S., the fungus is most frequently found in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys (Figure). In some enzootic areas, histoplasmosis is the most common systemic mycosis in animals. Between 1964 and 1976, 14 schools of veterinary medicine in the United States and Canada participated in a study of systemic mycoses in dogs and noted rates per hundred thousand patient years of 62 for histoplasmosis, 25 for blastomycosis and 17 for coccidioidomycosis [1Selby LA, Becker SV, Hayes HW, Jr. Epidemiologic risk factors associated with canine systemic mycoses. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:133-139.]. However, cases have been reported from non-enzootic areas, including in cats and raccoons from California [14Johnson LR, Fry MM, Anez KL, et al. Histoplasmosis infection in two cats from California. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40:165-169., 15Clothier KA, Villanueva M, Torain A, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in two juvenile raccoons (Procyon lotor) from a nonendemic region of the United States. J Vet Diagn Invest 2014;26:297-301.]. In Kentucky, 47% of dogs and 50% of thoroughbred horses exhibited Histoplasma skin test reactivity, while only 7.3% of horses demonstrated Blastomyces skin test reactivity [16Marx MB, Eastin CE, Turner C, et al. The influence of amphotericin B upon Histoplasma infection in dogs. Arch Environ Health 1970;21:649-655., 17Marx MB, Jones MB, Kimberlin DS, et al. Survey of histoplasmin and blastomycin test reactors among thoroughbred horses in central Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:1701-1705.]. Histoplasmosis was twice as frequent in animals from rural than from urban areas [3Turner C, Smith CD, Furcolow ML. Frequency of isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis from dogs in Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:137-141.].

CDC map of estimated areas with histoplasmosis

Several dog breeds have been shown to have an increased risk of histoplasmosis, including the Pointer, Weimaraner and Brittany [1Selby LA, Becker SV, Hayes HW, Jr. Epidemiologic risk factors associated with canine systemic mycoses. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:133-139.]. Mean age at diagnosis from one large study was 3.6 years [1Selby LA, Becker SV, Hayes HW, Jr. Epidemiologic risk factors associated with canine systemic mycoses. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:133-139.]. This older study indicated that cats had a similar incidence of histoplasmosis as that seen in dogs, but in certain areas, cats are at least 4 times as likely to have histoplasmosis (personal communication) [1Selby LA, Becker SV, Hayes HW, Jr. Epidemiologic risk factors associated with canine systemic mycoses. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:133-139.]. Persian cats are slightly over-represented in older studies, while Siamese cats are marginally under-represented [18Ackerman N, Cornelius LM, Halliwell WH. Respiratory distress associated with Histoplasma-induced tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1973;163:963-967.]. Interestingly, indoor-only cats remain at risk for histoplasmosis [19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 20]. Cases also occur in horses [21Katayama Y, Kuwano A, Yoshihara T. Histoplasmosis in the lung of a race horse with yersiniosis. J Vet Med Sci 2001;63:1229-1231., 22Panciera RJ. Histoplasmic (Histoplasma capsulatum) infection in a horse. The Cornell veterinarian 1969;59:306-312., 23Soliman R, Saad MA, Refai M. Studies on histoplasmosis farciminosii (epizootic lymphangitis) in Egypt. III. Application of a skin test (‘Histofarcin’) in the diagnosis of epizootic lymphangitis in horses. Mykosen 1985;28:457-461., 24Abou-Gabal M, Hassan FK, Al-Siad AA, et al. Study on equine histoplasmosis “epizootic lymphangitis”. Mykosen 1983;26:145-151., 25al-Ani FK. Epizootic lymphangitis in horses: a review of the literature. Rev Sci Tech 1999;18:691-699., 26Blackford J. Superficial and deep mycoses in horses. Vet Clin North Am Large Anim Pract 1984;6:47-58., 27Conti-Diaz IA, Alvarez BJ, Gezuele E, et al. [Intradermal reaction survey with paracoccidioidin and histoplasmin in horses]. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo 1972;14:372-376., 28Cooper VL, Kennedy GA, Kruckenberg SM, et al. Histoplasmosis in a miniature Sicilian burro. J Vet Diagn Invest 1994;6:499-501., 29Goetz TE, Coffman JR. Ulcerative colitis and protein losing enteropathy associated with intestinal salmonellosis and histoplasmosis in a horse. Equine Vet J 1984;16:439-441., 30Hall AD. An equine abortion due to histoplasmosis. Veterinary medicine, small animal clinician : VM, SAC 1979;74:200-201., 31Jones MB, Gonzalez-Ochoa A, Marx MB, et al. Survey of histoplasmin skin test reactions among horses in Mexico. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:1707-1709., 32Rezabek GB, Donahue JM, Giles RC, et al. Histoplasmosis in horses. J Comp Pathol 1993;109:47-55.], llamas [33Woolums AR, DeNicola DB, Rhyan JC, et al. Pulmonary histoplasmosis in a llama. J Vet Diagn Invest 1995;7:567-569.], sea mammals [34Burek-Huntington KA, Gill V, Bradway DS. Locally acquired disseminated histoplasmosis in a northern sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) in Alaska, USA. J Wildl Dis 2014;50:389-392., 35Jensen ED, Lipscomb T, Van Bonn B, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in an Atlantic bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). J Zoo Wildl Med 1998;29:456-460., 36Wilson TM, Kierstead M, Long JR. Histoplasmosis in a harp seal. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1974;165:815-817.], exotic pets and wild animals [15Clothier KA, Villanueva M, Torain A, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in two juvenile raccoons (Procyon lotor) from a nonendemic region of the United States. J Vet Diagn Invest 2014;26:297-301., 37Frame SR, Mehdi NA, Turek JJ. Naturally occurring mucocutaneous histoplasmosis in a rabbit. J Comp Pathol 1989;101:351-354., 38Jensen HE, Bloch B, Henriksen P, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a badger (Meles meles) in Denmark. APMIS 1992;100:586-592., 39Bauder B, Kubber-Heiss A, Steineck T, et al. Granulomatous skin lesions due to histoplasmosis in a badger (Meles meles) in Austria. Med Myc 2000;38:249-253., 40Eisenberg T, Seeger H, Kasuga T, et al. Detection and characterization of Histoplasma capsulatum in a German badger (Meles meles) by ITS sequencing and multilocus sequencing analysis. Med Myc 2013;51:337-344., 41Highland MA, Chaturvedi S, Perez M, et al. Histologic and molecular identification of disseminated Histoplasma capsulatum in a captive brown bear (Ursus arctos). J Vet Diagn Invest 2011;23:764-769., 42Raju NR, Langham RF, Bennett RR. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a Fennec fox. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986;189:1195-1196., 43Weller RE, Dagle GE, Malaga CA, et al. Hypercalcemia and disseminated histoplasmosis in an owl monkey. J Med Primatol 1990;19:675-680., 44Baskin GB. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a SIV-infected rhesus monkey. J Med Primatol 1991;20:251-253., 45Butler TM, Gleiser CA, Bernal JC, et al. Case of disseminated African histoplasmosis in a baboon. J Med Primatol 1988;17:153-161., 46Butler TM, Hubbard GB. An epizootic of histoplasmosis duboisii (African histoplasmosis) in an American baboon colony. Lab Anim Sci 1991;41:407-410., 47Brandao J, Woods S, Fowlkes N, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis (Histoplasma capsulatum) in a pet rabbit: case report and review of the literature. J Vet Diagn Invest 2014;26:158-162., 48Woolf A, Gremillion-Smith C, Sundberg JP, et al. Histoplasmosis in a striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis Schreber) from southern Illinois. J Wildl Dis 1985;21:441-443.].

PATHOGENESIS

Histoplasmosis is caused by inhalation of microconidia or hyphal fragments. Although intestinal lesions are prominent in dogs with disseminated histoplasmosis, experimental infection by gastric inoculation failed to induce disease in dogs [49Farrell RL, Cole CR, Prior JA, et al. Experimental Histoplasmosis, I. Methods for Production of Histoplasmosis in Dogs. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 1953;84:51-54.]. All mammals are susceptible to histoplasmosis, but cases have been reported most often in dogs, cats, and horses. Birds, because of their higher body temperature, are not susceptible to natural infection but may be infected experimentally, causing infection localized to feather tips [50Tewari RP, Campbell CC. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from feathers of chickens inoculated intravenously and subcutaneously with the yeast phase of the organism. Sabouraudia 1965;4:17-22., 51Emmons CW, Rowley DA, Olson BJ, et al. Histoplasmosis; proved occurrence of inapparent infection in dogs, cats and other animals. Am J Hygiene 1955;61:40-44.].

Cellular immunity is critical in defense against H. capsulatum, based on analysis of risk factors for severe disease [52Horwath MC, Fecher RA, Deepe GS, Jr. Histoplasma capsulatum, lung infection and immunity. Future Microbiol 2015;10:967-975.]. The microconidia are inhaled and attract dendritic cells, neutrophils and macrophages, which phagocytose the organism that then transform into yeasts and multiply unchecked in the non-immune subject. During the first two weeks, the infection progresses and disseminates hematogenously throughout the reticuloendothelial system. By day 14 of infection, specific T cell immunity develops, halting proliferation of the yeast and progression of the infection. Evidence for self-limited dissemination includes demonstration of calcified granulomas in the spleen and liver in healthy individuals in endemic areas for histoplasmosis, which contain non-viable organisms and occasional isolation of H. capsulatum from extrapulmonary specimens in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

Cytokines that are most important in immunity to H. capsulatum include IL-12, IL-18, TNF-α and interferon-γ. A successful T cell response requires dendritic cells, CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes and activated macrophages.

T cells produce interferon-γ and TNF-α, which activate macrophages to kill Histoplasma yeast. The importance of TNF-α in humans is highlighted by the emerging recognition of histoplasmosis as a major opportunistic infection in patients treated with TNF inhibitors [53Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis Complicating Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Blocker Therapy: A Retrospective Analysis of 98 Cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:409-417., 54Hage CA, Bowyer S, Tarvin SE, et al. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:85-92.].

While histoplasmosis is self-limited in over 95% of healthy humans, chronic and/or progressive disease may occur more common in animals. However, 31% to 44% of euthanized dogs and cats in enzootic areas had culture evidence for chronic histoplasmosis, suggesting sub-clinical infections do occur [2Fattal AR, Schwarz J, Straub M. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from lymph nodes of spontaneously infected dogs. Am J Clin Pathol 1961;36:119-124., 55Rowley DA, Haberman RT, Emmons CW. Histoplasmosis: pathologic studies of fifty cats and fifty dogs from Loudoun County, Virginia. J Infect Dis 1954;95:98-108., 56Turner C, Smith CD, Furcolow ML. The efficiency of serologic and cultural methods in the detection of infection with Histoplasma and Blastomyces in mongrel dogs. Sabouraudia 1972;10:1-5.].

A study of newborn mongrel puppies experimentally infected with Blastomyces dermatitidis provides insight into immunity to blastomycosis and histoplasmosis [57Smith CD, Furcolow ML, Hulker P. Effect of immunosuppressants on dogs exposed two and one-half years previously to Blastomyces dermatitidis. Am J Epidemiol 1976;104:299-305.]. Thirty-three puppies were obtained from a non-enzootic area (Cheyenne, Wyoming) and exposed to soil inoculated with B. dermatitidis. The puppies were exposed to the soil in a wooden shed for 2 days and then were housed in cages near the shed for 8 weeks. Six dogs died, three of which had positive cultures for Blastomyces, including one with positive cultures for Histoplasma. The survivors (N=27) remained healthy. One third of the dogs were autopsied at the 119th week following infection and used as controls and 18 dogs were immunosuppressed with azathioprine and prednisone. The immunosuppressed dogs were autopsied at the 130th week following exposure and tissues were cultured for fungus. Histoplasma was isolated from the tissues in 14/18 dogs (78%) and Blastomyces was isolated from none. The study was conducted in central Kentucky, a highly enzootic area for histoplasmosis, and enzootic exposure was the mode of infection. These findings show that the immune response in dogs was adequate to prevent chronic blastomycosis but not histoplasmosis. This also differs from immunity in humans, where prior exposure induces long-lasting protection against reinfection, reactivation or relapse [54Hage CA, Bowyer S, Tarvin SE, et al. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:85-92.].

Like dogs, chronic histoplasmosis also is common in bats. [58Greer DL, McMurray DN. Pathogenesis of experimental histoplasmosis in the bat, Artibeus lituratus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1981;30:653-659., 59Tesh RB, Schneidau JD, Jr. Experimental infection of North American insectivorous bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) with Histoplasma capsulatum. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1966;15:544-550.] Interestingly the tissue reaction in bats is minimal or absent, possibly explaining their inability to eradicate the organism [58Greer DL, McMurray DN. Pathogenesis of experimental histoplasmosis in the bat, Artibeus lituratus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1981;30:653-659., 59Tesh RB, Schneidau JD, Jr. Experimental infection of North American insectivorous bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) with Histoplasma capsulatum. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1966;15:544-550., 60Hasenclever HF, Shacklette MH, Hunter AW, et al. The use of cultural and histologic methods for the detection of Histoplasma capsulatum in bats: absence of a cellular response. Am J Epidemiol 1969;90:77-83., 61Taylor ML, Chavez-Tapia CB, Vargas-Yanez R, et al. Environmental conditions favoring bat infection with Histoplasma capsulatum in Mexican shelters. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;61:914-919.]. The infection rate varies markedly in different genera of bats, suggesting genetic differences in susceptibility [62Klite PD, Diercks FH. Histoplasma Capsulatum in Fecal Contents and Organs of Bats in the Canal Zone. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1965;14:433-439.]. In one study, Histoplasma was not isolated from wild-caught mice, suggesting that their immune response is able to eliminate the organism [51Emmons CW, Rowley DA, Olson BJ, et al. Histoplasmosis; proved occurrence of inapparent infection in dogs, cats and other animals. Am J Hygiene 1955;61:40-44.].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The severity of clinical manifestations correlates with the intensity of exposure (size of inoculum) and the underlying health of the exposed individual. Cole described rapidly progressive fatal course over two to four weeks in 10% of dogs with histoplasmosis, and chronic progressive course over two to 20 months in 90% [63Cole CR, Farrell RL, Chamberlain DM, et al. Histoplasmosis in animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1953;122:471-473.]. Demonstration of positive cultures of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tissues of apparently healthy dogs and cats from enzootic areas suggest that the clinical findings may be overlooked in many cases [2Fattal AR, Schwarz J, Straub M. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from lymph nodes of spontaneously infected dogs. Am J Clin Pathol 1961;36:119-124., 3Turner C, Smith CD, Furcolow ML. Frequency of isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis from dogs in Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:137-141., 64Rowley DA. Pathological studies of histoplasmosis; preliminary report on fifty cats and fifty dogs from Loudoun County, Virginia. Public health monograph 1956;39:268-271.]. In one study, 44% of 100 consecutive adult dogs and cats that underwent voluntary euthanasia and complete necropsy with pathology and culture of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tissues, exhibited evidence for active histoplasmosis [55Rowley DA, Haberman RT, Emmons CW. Histoplasmosis: pathologic studies of fifty cats and fifty dogs from Loudoun County, Virginia. J Infect Dis 1954;95:98-108.]. Noteworthy was that fact that only five dogs were known to have had histoplasmosis during the previous seven years.

Pulmonary

Pneumonia, as part of progressive disseminated disease, is one of the most common manifestation of histoplasmosis, described in 72% of dogs in which thoracic radiographs were performed obtained [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209.]. Dogs often present with dyspnea, cough, fever, and lethargy. Radiographs showed interstitial disease in 44%, alveolar disease in 12%, bronchial disease in 10%, and a mixed pattern in 16%. Interstitial disease was most often characterized as diffuse (68%) and “miliary” or structured interstitial in 14%, respectively [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209.].

Pneumonia is the most common manifestation in cats occurring in 39-44% of cases [65Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in cats: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987;190:1445-1448., 66Davies C, Troy GC. Deep mycotic infections in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1996;32:380-391., 67Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:182-187.]. Symptoms include dyspnea, tachypnea and less commonly cough [19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 67Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:182-187.]. Diffuse interstitial infiltrates or lung nodules were described in 40-67% cases, miliary infiltrates in 6-17%, and alveolar infiltrates in 13-17% [19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 67Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:182-187.]. Nasal discharge also was described [67Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:182-187.]. Sneezing occurs in some cases (personal communications).

Mediastinal lymphadenitis

Less commonly, no lung abnormalities were noted but sternal (12%), tracheobronchial (6%), or cranial mediastinal lymphadenopathy (2%) or pleural effusions (8%) were noted [18Ackerman N, Cornelius LM, Halliwell WH. Respiratory distress associated with Histoplasma-induced tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1973;163:963-967.]. These may impinge upon the airways and cause cough and respiratory distress [18Ackerman N, Cornelius LM, Halliwell WH. Respiratory distress associated with Histoplasma-induced tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1973;163:963-967., 68Schulman RL, McKiernan BC, Schaeffer DJ. Use of corticosteroids for treating dogs with airway obstruction secondary to hilar lymphadenopathy caused by chronic histoplasmosis: 16 cases (1979-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;214:1345-1348.]. Radiographs showed tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy usually accompanied by interstitial pneumonia. The outcome has ranged from spontaneous resolution, resolution with corticosteroid treatment alone or combined with antifungal therapy, and progressive obstruction of the airways and death [68Schulman RL, McKiernan BC, Schaeffer DJ. Use of corticosteroids for treating dogs with airway obstruction secondary to hilar lymphadenopathy caused by chronic histoplasmosis: 16 cases (1979-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;214:1345-1348.]. Concurrent dissemination may occur [18Ackerman N, Cornelius LM, Halliwell WH. Respiratory distress associated with Histoplasma-induced tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1973;163:963-967.].

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis

Much of the information is derived from reports in cats. Fever, weight loss, reduced activity, anemia, and interstitial lung disease are the most common manifestations in cats, (Table 1) [12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073., 19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 65Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in cats: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987;190:1445-1448.]. Pulmonary involvement occurs in many cases and is usually manifested as tachypnea and dyspnea. Radiographs typically show diffuse interstitial or miliary or nodular infiltrates. Bone and joint involvement are more common as compared with dogs [11Fielder SE, Meinkoth JH, Rizzi TE, et al. Feline histoplasmosis presenting with bone and joint involvement: clinical and diagnostic findings in 25 cats. J Feline Med Surg 2019;21:887-892., 20]. In addition, bone marrow involvement, causing cytopenia of one or multiple cell lines, is also relatively more common in cats as compared with dogs. Abnormal physical findings include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, eye lesions or discharge, nasal discharge, subcutaneous nodules, and skin lesions. The untreated course ranges from subclinical, chronic infection to a rapidly fatal illness. In dogs, diarrhea, intestinal blood loss, anemia and reduced activity predominate [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 63Cole CR, Farrell RL, Chamberlain DM, et al. Histoplasmosis in animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1953;122:471-473., 69Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in dogs: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;193:1443-1447.]. It is common for clinical manifestations to be limited to GI disease. Tissues commonly involved at necropsy include liver, spleen, abdominal lymph nodes, large intestine, and less frequently CNS, ocular, bone/joints, bone marrow, adrenal glands, kidneys, and pancreas [63Cole CR, Farrell RL, Chamberlain DM, et al. Histoplasmosis in animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1953;122:471-473., 69Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in dogs: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;193:1443-1447., 70Lau RE, Kim SN, Pirozok RP. Histoplasma capsulatum infection in a metatarsal of a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1978;172:1414-1416.].

Equine abortion

Infections in the fetus or neonatal foal may occur, causing abortion or early foal death [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 20Ludwig HC, Hanzlicek AS, KuKanich KS, et al. Candidate prognostic indicators in cats with histoplasmosis treated with antifungal therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2018;20:985-996., 30Hall AD. An equine abortion due to histoplasmosis. Veterinary medicine, small animal clinician : VM, SAC 1979;74:200-201., 32Rezabek GB, Donahue JM, Giles RC, et al. Histoplasmosis in horses. J Comp Pathol 1993;109:47-55., 71Saunders JR, Matthiesen RJ, Kaplan W. Abortion due to histoplasmosis in a mare. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983;183:1097-1099., 72Hodges RD, Legendre AM, Adams LG, et al. Itraconazole for the treatment of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 1994;8:409-413.]. Pulmonary and disseminated involvement usually are present in the fetus or newborn [32Rezabek GB, Donahue JM, Giles RC, et al. Histoplasmosis in horses. J Comp Pathol 1993;109:47-55.]. In most cases, the mare appears healthy, but the placenta is involved.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

Common laboratory abnormalities include anemia, leukopenia, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperglobulinemia, increased liver enzymes and bilirubin, creatinine elevation, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia (Table 2) [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073., 19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 20Ludwig HC, Hanzlicek AS, KuKanich KS, et al. Candidate prognostic indicators in cats with histoplasmosis treated with antifungal therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2018;20:985-996., 65Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in cats: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987;190:1445-1448., 67Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:182-187., 69Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in dogs: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;193:1443-1447., 72Hodges RD, Legendre AM, Adams LG, et al. Itraconazole for the treatment of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 1994;8:409-413.]. Hypocalcemia usually correlates with hypoalbuminemia. Hypercalcemia is caused by dysregulated production of 1,25-(OH2)D3 (calcitriol) by macrophages in alveoli and other areas of granulomatous inflammation and may be accompanied by angiotensin-converting enzyme elevation, leading to a misdiagnosis of sarcoidosis and inappropriate treatment with corticosteroids in humans [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 73Liang KV, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis with tenosynovitis of the hand and hypercalcemia mimicking sarcoidosis. J Clin Rheumatol 2004;10:138-142.].

DIAGNOSIS

Prompt diagnosis offers the greatest chance for recovery from histoplasmosis, made possible by early therapy [74Balows A, Ausherman RJ, Hopper JM. Practical diagnosis and therapy of canine histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1966;148:678-684.]. Today most cases are diagnosed by detection of Histoplasma antigen in the urine and/or serum or demonstration of yeast in the bodily fluids or tissues [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073., 75Cook AK, Cunningham LY, Cowell AK, et al. Clinical evaluation of urine Histoplasma capsulatum antigen measurement in cats with suspected disseminated histoplasmosis. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:512-515., 76Cunningham L, Cook A, Hanzlicek A, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of Histoplasma Antigen Detection by Enzyme Immunoassay. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2015;51:306-310., 77Rothenburg L, Hanzlicek AS, Payton ME. A monoclonal antibody-based urine Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (IMMY(R)) for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2019;33:603-610.]. Antibody detection may be useful in cases in which antigen tests and/or pathology are negative or specimens are not available for pathology. Currently comparative studies evaluating pathology, culture, antigen and antibody detection are unavailable.

Cytopathology or Histopathology

Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration of readily accessible lesions for cytopathology or histopathology may provide the quickest and most accurate basis for diagnosis and may be positive in cases with negative antigen results. Cytology of rectal scrapings may be positive in cases with intestinal involvement [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209.].

Culture

Fungal culture may be positive in those with negative pathology. Its major limitation is the slow growth rate requiring 4-6 weeks for culture results in many cases. And there may be a small risk of human exposure by sharp injuries while handling the tissue in the clinic or pathology laboratory.

Antigen detection

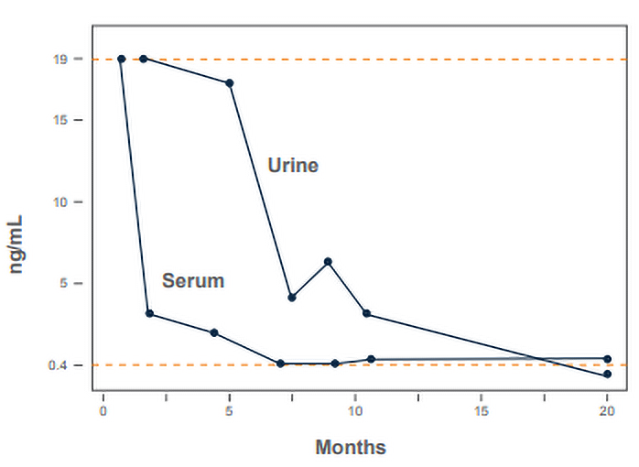

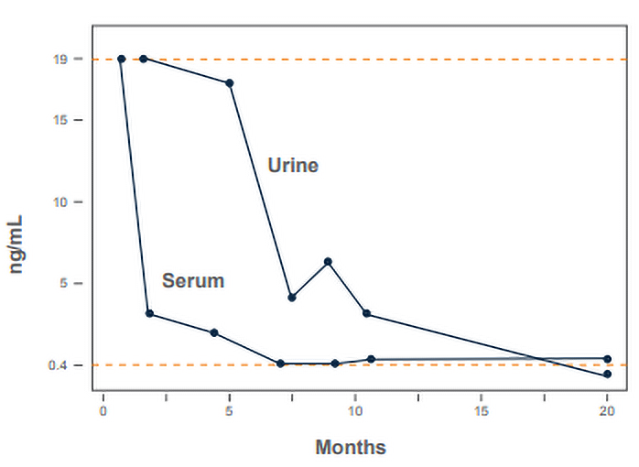

A galactomannan antigen in the cell wall of proliferating Histoplasma yeasts is released into the tissues and blood and excreted in the urine. Antigen was detected in the urine of 94% of cats and 92% of dogs (unpublished data) with histoplasmosis [75Cook AK, Cunningham LY, Cowell AK, et al. Clinical evaluation of urine Histoplasma capsulatum antigen measurement in cats with suspected disseminated histoplasmosis. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:512-515., 76Cunningham L, Cook A, Hanzlicek A, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of Histoplasma Antigen Detection by Enzyme Immunoassay. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2015;51:306-310., 77Rothenburg L, Hanzlicek AS, Payton ME. A monoclonal antibody-based urine Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (IMMY(R)) for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2019;33:603-610.]. The highest sensitivity is achieved by testing both urine and serum: Antigen may be positive in the serum but negative in the urine [78Jarchow A, Hanzlicek A. Antigenemia without antigenuria in a cat with histoplasmosis. JFMS Open Rep 2015;1:2055116915618422.]. Antigen also may be detected in the respiratory secretions in humans with pulmonary histoplasmosis and cerebrospinal fluid of those with meningitis. Antigen levels decline during treatment and increase with relapse, providing a tool for monitoring therapy [12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073.].

Commercially available Histoplasma antigen agent specific reagents (IMMY, HISTOPLASMA GM EIA) have been studied in cats [77Rothenburg L, Hanzlicek AS, Payton ME. A monoclonal antibody-based urine Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (IMMY(R)) for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2019;33:603-610.]. Using a 1.1 ng/mL diagnostic cut off, sensitivity was 77% and specificity was 97%. Using a 0.25ng/mL cut off, sensitivity was 89% and specificity 80%. By comparison, sensitivity of the MiraVista Histoplasma antigen EIA was 94% and specificity 96%. The MiraVista assay has been validated for quantification and used for treatment monitoring. The agent specific reagents have not been validated for treatment monitoring.

The antigen found in histoplasmosis cross reacts with that found in blastomycosis [79Spector D, Legendre AM, Wheat J, et al. Antigen and antibody testing for the diagnosis of blastomycosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:839-843.]. Furthermore, the clinical findings and enzootic distribution overlap. Thus, differentiation of the two mycoses may be difficult, but treatment is similar, in many cases reducing the need to distinguish the two organisms. Antibody testing using Histoplasma IgG and Blastomyces IgG antibody enzyme-immunoassays (EIA) may distinguish these two mycoses [80Richer SM, Smedema ML, Durkin MM, et al. Development of a highly sensitive and specific blastomycosis antibody enzyme immunoassay using Blastomyces dermatitidis surface protein BAD-1. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014;21:143-146.].

Antibody detection

Antibody detection has been infrequently used for diagnosis in veterinary medicine. Historically, only complement fixation (CF) and agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) methods have been available. The sensitivity of CF was 90% in one report and 11% in another [57Smith CD, Furcolow ML, Hulker P. Effect of immunosuppressants on dogs exposed two and one-half years previously to Blastomyces dermatitidis. Am J Epidemiol 1976;104:299-305., 81Mitchell M, Stark DR. Disseminated canine histoplasmosis: a clinical survey of 24 cases in Texas. Can Vet J 1980;21:95-100.]. The CF test is often uninterpretable in dogs because their serum is anti-complementary, and CF is not offered commercially at veterinary reference laboratories. Agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) is offered commercially, but studies have not been conducted to establish sensitivity and specificity.

Sensitivity may be improved using an IgG anti-Histoplasma antibody EIA developed at MiraVista Diagnostics. The sensitivity in dogs and cats was 78% and the specificity was 97% in dogs and 84% in cats (data on file, MiraVista Diagnostics).

Clinical situations to consider antibody testing:

- When histoplasmosis is suspected but antigen testing is negative or low positive (<1 ng/mL)

- When differentiation between histoplasmosis and blastomycosis or other (cross-reacting) organism is clinically indicated

- To determine exposure to Histoplasma for point-source outbreaks or other environmental investigations

Molecular techniques

PCR has been reported to be positive in the tissues in dogs with histoplasmosis and in other species [34Burek-Huntington KA, Gill V, Bradway DS. Locally acquired disseminated histoplasmosis in a northern sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) in Alaska, USA. J Wildl Dis 2014;50:389-392., 35Jensen ED, Lipscomb T, Van Bonn B, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in an Atlantic bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). J Zoo Wildl Med 1998;29:456-460., 41Highland MA, Chaturvedi S, Perez M, et al. Histologic and molecular identification of disseminated Histoplasma capsulatum in a captive brown bear (Ursus arctos). J Vet Diagn Invest 2011;23:764-769., 82Pratt CL, Sellon RK, Spencer ES, et al. Systemic mycosis in three dogs from nonendemic regions. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:411-416., 83Reginato A, Giannuzzi P, Ricciardi M, et al. Extradural spinal cord lesion in a dog: first case study of canine neurological histoplasmosis in Italy. Vet Microbiol 2014;170:451-455., 84Reyes-Montes MR, Rodriguez-Arellanes G, Perez-Torres A, et al. Identification of the source of histoplasmosis infection in two captive maras (Dolichotis patagonum) from the same colony by using molecular and immunologic assays. Rev Argent Microbiol 2009;41:102-104., 85Sano A, Ueda Y, Inomata T, et al. [Two cases of canine histoplasmosis in Japan]. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 2001;42:229-235., 86Ueda Y, Sano A, Tamura M, et al. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis by detection of the internal transcribed spacer region of fungal rRNA gene from a paraffin-embedded skin sample from a dog in Japan. Vet Microbiol 2003;94:219-224., 87Schumacher LL, Love BC, Ferrell M, et al. Canine intestinal histoplasmosis containing hyphal forms. J Vet Diagn Invest 2013;25:304-307.]. Most reports describe results in single cases and no studies have reported the sensitivity and specificity or results in bodily fluids. No studies have compared PCR to other antigen detection. Additional studies are needed to assess the role of molecular diagnostics for histoplasmosis.

TREATMENT

Guidelines for treatment are presented here and in Infectious Diseases of Dogs and Cats [88Sykes JE and Toboada J. Histoplasmosis. in Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. Sykes JE Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2019.].

Amphotericin B

Amphotericin B is the treatment of choice in severe cases in humans and induces a clinical response more rapidly than itraconazole [89Hage CA, Kirsch EJ, Stump TE, et al. Histoplasma antigen clearance during treatment of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS determined by a quantitative antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011;18:661-666.]. Reasons that amphotericin B is effective includes its fungicidal mode of action and intravenous route of administration, rapidly providing therapeutic blood concentrations. Administration of amphotericin B initially may improve early survival, after which treatment could be transitioned to itraconazole. Lipid/ liposomal forms of amphotericin B are better tolerated but are more expensive than the deoxycholate formulation. Renal function and serum electrolytes should be monitored during treatment.

Anti-inflammatory treatment with low doses of corticosteroids may be helpful in reducing systemic side effects of amphotericin B [90Plumb D. Amphotericin B. in Veterinary Drug Handbook. 9th ed. Stockholm, WI: Pharma Vet Inc.; 2018.]. Some veterinarians recommend use of corticosteroids to prevent clinical worsening after initiation of treatment attributed to an inflammatory reaction to antigens released from “dying” Histoplasma organisms (personal communications) [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 20].

Itraconazole

The usual dosage in dogs is approximately 5 mg/kg/day after a 3 day loading phase at 10 mg/kg/day [91Legendre AM, Rohrbach BW, Toal RL, et al. Treatment of blastomycosis with itraconazole in 112 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 1996;10:365-371.]. The usual dosage with cats is 10 mg/kg/day with capsule and 7.5 mg/kg/day with solution [92Mawby DI, Whittemore JC, Fowler LE, et al. Comparison of absorption characteristics of oral reference and compounded itraconazole formulations in healthy cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:195-200.]. At least 6 months of therapy is recommended [88Sykes JE and Toboada J. Histoplasmosis. in Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. Sykes JE Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2019.]. A retrospective study in dogs reported that 71% (17/24) responded to itraconazole and 17% relapsed [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209.]. Combining data from 3 retrospective studies in cats, 68/79 (86%) of those treated with itraconazole survived to hospital discharge [19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 20Ludwig HC, Hanzlicek AS, KuKanich KS, et al. Candidate prognostic indicators in cats with histoplasmosis treated with antifungal therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2018;20:985-996., 72Hodges RD, Legendre AM, Adams LG, et al. Itraconazole for the treatment of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 1994;8:409-413.]. Since histoplasmosis is often chronic and requires long term treatment, longer term survival is arguably more important, and in one study, 6-month survival with itraconazole was 35/53 (66%) [20Ludwig HC, Hanzlicek AS, KuKanich KS, et al. Candidate prognostic indicators in cats with histoplasmosis treated with antifungal therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2018;20:985-996.]. Relapse rates were reported in 3 studies and occurred in 8/36 (22%) of cats receiving itraconazole [12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073., 19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 72Hodges RD, Legendre AM, Adams LG, et al. Itraconazole for the treatment of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 1994;8:409-413.]. Retrospective design, small sample size and inclusion of cases spanning over many years were limitations of some of these studies. A prospective study in humans with AIDS reported an 85% (50/59) response rate and no relapses: Only 2 of the failures were attributed to progressive histoplasmosis and itraconazole blood levels were below 2.0 µg/mL in both [93Wheat J, Hafner R, Korzun AH, et al. Itraconazole treatment of disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS Clinical Trial Group. Am J Med 1995;98:336-342.].

Generic FDA approved itraconazole capsules are preferred as it achieves similar blood levels to the brand-name Sporanox® (Janssen Pharmaceuticals) and is considerably less expensive [94Mawby DI, Whittemore JC, Genger S, et al. Bioequivalence of orally administered generic, compounded, and innovator-formulated itraconazole in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:72-77.]. An itraconazole solution (Itrafungol®) is labeled for the treatment of dermatophytosis in cats and is essentially identical to Sporanox® solution. Compounded powder formulations (capsule or solution) have poor bioavailability [13Renschler J, Albers A, Sinclair-Mackling H, et al. Comparison of Compounded, Generic, and Innovator-Formulated Itraconazole in Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018;54:195-200., 95Mazepa AS, Trepanier LA, Foy DS. Retrospective comparison of the efficacy of fluconazole or itraconazole for the treatment of systemic blastomycosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:440-445.] and are not recommended in either species [13Renschler J, Albers A, Sinclair-Mackling H, et al. Comparison of Compounded, Generic, and Innovator-Formulated Itraconazole in Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018;54:195-200., 88Sykes JE and Toboada J. Histoplasmosis. in Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. Sykes JE Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2019., 95Mazepa AS, Trepanier LA, Foy DS. Retrospective comparison of the efficacy of fluconazole or itraconazole for the treatment of systemic blastomycosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:440-445.]. If needed for smaller animals, FDA approved capsules can be opened, weighed and separated, and placed in smaller capsules. Alternatively, a 100 mg capsule every other day might be appropriate for cats [95Mazepa AS, Trepanier LA, Foy DS. Retrospective comparison of the efficacy of fluconazole or itraconazole for the treatment of systemic blastomycosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:440-445.]. Blood levels should be measured 14 (dogs) to 21 (cats) days after beginning therapy, and the preferred range is 2-7 µg/mL as measured by bioassay, and at least 1.0-2.0 µg/mL by HPLC or LC-MS. Bioassay levels above 7.0 µg/mL cause more toxicity and are unnecessary. Oral bioavailability of the capsule is increased by a recent meal and decreased by concurrent administration of an antacid. Inability to achieve therapeutic concentration, intolerable side effects, drug-to-drug interactions, and lack of clinical improvement during treatment are reasons to switch to another triazole.

Itraconazole may cause a variety of adverse effects, most commonly loss of appetite, anorexia, vomiting, or diarrhea, which may be related to high blood levels [96Lestner JM, Roberts SA, Moore CB, et al. Toxicodynamics of itraconazole: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:928-930.]. Bilirubin and hepatic enzymes also may be elevated, in association with clinical evidence for hepatitis in some cases and should be monitored during therapy. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) greater than 200 U/L may warrant discontinuation of itraconazole [97Legendre AM. Blastomycosis. in Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Greene C. Ed. Fourth ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012.]. Itraconazole may be restarted at half of the former dose, based on trough itraconazole blood levels. Ulcerative dermatitis was observed in 7.5% of dogs receiving itraconazole at 10 mg/kg/day [97Legendre AM. Blastomycosis. in Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Greene C. Ed. Fourth ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012.].

Fluconazole

Studies in cats and dogs were retrospective and small, preventing accurate assessment of the effectiveness of fluconazole therapy [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848., 20]. Relapse rates were 22% and 17% for cats and dogs, respectively [9Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209., 19Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848.]. Fluconazole and itraconazole susceptibility were assessed in Histoplasma isolates from humans who failed fluconazole: Resistance developed to fluconazole in 59% of failure isolates and cross resistance was observed to voriconazole [98Wheat LJ, Connolly P, Smedema M, et al. Activity of newer triazoles against Histoplasma capsulatum from patients with AIDS who failed fluconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;57:1235-1239., 99Wheat LJ, Connolly P, Smedema M, et al. Emergence of resistance to fluconazole as a cause of failure during treatment of histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency disease syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:1910-1913.]. Given the inherent relative low sensitivity, and potential for acquired resistance, it is considered a secondline choice for oral antifungal treatment of histoplasmosis in dogs and cats. In the clinical scenario where itraconazole is not well tolerated, or the cost of itraconazole precludes its use, fluconazole should be considered. To help decrease the chance of acquired resistance, an appropriate dose (20 mg/kg/day in dogs or 100 mg/day in cats) and duration (at least 6 months) of FDA approved drug should be used. Unlike itraconazole, oral bioavailability is not affected by recent meal or concurrent antacid administration.

Other azoles

Ketoconazole is infrequently used as it is not effective. One of 5 cats with histoplasmosis, in one study, responded to ketoconazole [100Kabli S, Koschmann JR, Robertstad GW, et al. Endemic canine and feline histoplasmosis in El Paso, Texas. J Med Vet Mycol 1986;24:41-50.]. In small studies, posaconazole, voriconazole and isavuconazole have been used successfully in humans [101Restrepo A, Tobon A, Clark B, et al. Salvage treatment of histoplasmosis with posaconazole. J Infect 2007;54:319-327., 102Freifeld A, Proia L, Andes D, et al. Voriconazole use for endemic fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:1648-1651., 103Thompson GR, 3rd, Rendon A, Ribeiro Dos Santos R, et al. Isavuconazole Treatment of Cryptococcosis and Dimorphic Mycoses. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:356-362.]. The voriconazole study evaluated patients who discontinued other treatments because of intolerance or toxicity (8 patients) and increasing urinary antigen (1 patient): 3 patients improved and 6 remained stable [102Freifeld A, Proia L, Andes D, et al. Voriconazole use for endemic fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:1648-1651.]. Resistance to voriconazole has been observed in isolates from AIDS patients with histoplasmosis that failed treatment with fluconazole [98Wheat LJ, Connolly P, Smedema M, et al. Activity of newer triazoles against Histoplasma capsulatum from patients with AIDS who failed fluconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;57:1235-1239., 104Freifeld A, Arnold S, Ooi W, et al. Relationship of blood level and susceptibility in voriconazole treatment of histoplasmosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:2656-2657.]. The newer azoles are more expensive than itraconazole. Posaconazole and voriconazole have been used with success as salvage therapy for dogs and cats with histoplasmosis that have failed itraconazole and fluconazole therapy (unpublished data). Although early reports of neurotoxicity with voriconazole in cats has limited its use clinically, lower doses (12.5mg total every 72 hours) might be effective, while minimizing adverse effects [105Vishkautsan P, Papich MG, Thompson GR, 3rd, et al. Pharmacokinetics of voriconazole after intravenous and oral administration to healthy cats. Am J Vet Res 2016;77:931-939.].

Terbinafine

Histoplasma is susceptible to this allylamine antifungal agent [43Weller RE, Dagle GE, Malaga CA, et al. Hypercalcemia and disseminated histoplasmosis in an owl monkey. J Med Primatol 1990;19:675-680.]. Moreover a pharmacokinetic study in dogs showed adequate oral bioavailability [106Sakai MR, May ER, Imerman PM, et al. Terbinafine pharmacokinetics after single dose oral administration in the dog. Vet Derm 2011;22:528-534.]. Studies to evaluate its effectiveness in histoplasmosis are lacking, but some veterinarians use it in combination with other antifungals, as salvage therapy, in patients failing other treatments (personal communications).

Duration of treatment

The optimal duration of therapy is unclear as prospective studies have not been conducted. The duration of treatment in humans with disseminated or chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis is at least 12 months [107Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:807-825.]. Treatment for at least 6 months is recommended in dogs and cats [88Sykes JE and Toboada J. Histoplasmosis. in Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. Sykes JE Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2019.].

Adjunctive therapy

Schulman noted rapid clinical improvement in 10 dogs with mediastinal lymphadenitis causing airway obstruction that received corticosteroids, five of which also received antifungal treatment [68Schulman RL, McKiernan BC, Schaeffer DJ. Use of corticosteroids for treating dogs with airway obstruction secondary to hilar lymphadenopathy caused by chronic histoplasmosis: 16 cases (1979-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;214:1345-1348.]. Corticosteroids also may be helpful in cases of diffuse pulmonary histoplasmosis complicated by respiratory insufficiency and in cases of inflammatory CNS or ocular disease. Concurrent antifungal therapy is recommended to reduce the risk for progressive dissemination caused by corticosteroid-induced immunosuppression.

Antigen monitoring

Antigen should be tested in urine at least every 3 months during treatment, at 6 and 12 months after stopping treatment, and any time the clinical findings suggest recurrence. And if the urine antigen is “Above Limit of Quantification, ALQ” serum should be used for monitoring instead. When the serum antigen is negative, resume monitoring urine antigen until negative. Consultation should be obtained for questions about discontinuation of treatment and if antigen remains positive more than 12 months.

Failure of the antigen concentration to decline also raises concern about the effectiveness of treatment, which may be caused by inadequate itraconazole blood levels or development of resistance to fluconazole [12Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073.]. If itraconazole blood levels are subtherapeutic, the dosage should be increased, and blood levels should be rechecked 14-21 days later. An increase in antigen concentration after stopping treatment suggests recurrence. An example of antigen clearance in urine and serum is presented in the Figure below.

Table 1. Clinical Findings in Dogs and Cats with Histoplasmosis

| Finding |

Dog (%) |

Cat (%) |

| General/systemic |

| Fever |

20-60 |

25-50 |

| Inappetence |

20-60 |

40-50 |

| Lethargy/Depression |

60-70 |

35-70 |

| Weight Loss |

40-80 |

50-85 |

| Respiratory |

| Coughing |

10-20 |

10-20 |

| Dyspnea |

10-40 |

45-60 |

| Tachypnea |

30-40 |

35-50 |

| Epistaxis |

<10 |

<10 |

| Nasal discharge |

10-20 |

10-20 |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Diarrhea |

20-80 |

10-15 |

| Hematochezia |

20-30 |

<10 |

| Hepatomegaly* |

10-20 |

20-40 |

| Splenomegaly* |

10-40 |

20-40 |

| Icterus |

10-20 |

15-30 |

| Abdominal Lymphadenopathy |

20-50 |

30-40 |

| Miscellaneous |

| Mouth |

<10 |

<10 |

| Ocular |

5-40 |

5-25 |

| Neurologic |

5-10 |

<5 |

| Bone/joint |

10-30 |

15-30 |

| Peripheral Lymphadenopathy |

20-60 |

30-60 |

| Skin |

10-20 |

10-20 |

NR-not reported

*Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly often reported as abdominal organomegaly

Table 2. Laboratory Abnormalities in Dogs and Cats with Histoplasmosis

| Laboratory |

Dog (%) |

Cat (%) |

| Anemia |

30-100 |

35-55 |

| Thrombocytopenia* |

10-30 |

40-50 |

| Decreased WBC |

5-40 |

10-25 |

| Increased WBC |

5-40 |

5-20 |

| Increased ALT |

10-60 |

5-35 |

| Increased ALP |

10-50 |

<10 |

| Increased Bilirubin |

20-30 |

20-30 |

| Decreased Albumin |

80-100 |

30-40 |

| Increased Globulin |

25-50 |

10-20 |

| Increased Creatinine |

5-10 |

5-15 |

| Decreased Calcium |

30-40 |

10-45 |

| Increased Calcium |

5-25 |

5-25 |

*Platelet count often not reported due to platelet clumping in cats

Table 3. Sensitivity and Specificity of Histoplasma Antigen and Antibody Testing at MiraVista Diagnostics

| Test |

Specimen |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Reference |

| Histoplasma antigen |

Urine (dog)

Urine (cat) |

92%

94% |

99%

100% |

76, MVD

75 |

| Histoplasma IgG Antibody EIA |

Serum (dog)

Serum (cat) |

78%

78% |

97%

84% |

MVD

MVD |

Table 4. What Test(s) to Order for Histoplasmosis in Dogs and Cats

| Endemic |

Primary |

Secondary |

| Histoplasmosis |

Histoplasma urine antigen (code 310) |

Histoplasma IgG antibody (code 327-canine)

Histoplasma IgG antibody (code 328-feline)

Histoplasma FID antibody (code 321)

Histoplasma serum antigen (code 310) |

Table 5. Treatment Recommendations for Histoplasmosis in Dogs and Cats

Severe disease*Lipid or Liposome encapsulated Amphotericin B 1.0 mg/kg (dog) or 0.5 mg/kg (cat) IV 3 times a week or EODUp 24 mg/kg (dog) and 12 mg/kg (cat) cumulativeItraconazole as above6-12 months

| Category |

Daily Dose |

Duration |

| Dogs |

Itraconazole 5 mg/day BID for 3 days then SID |

6-12 months |

| Cats |

Itraconazole 5 mg/day BID or 10 mg/day SID^ |

6-12 months |

^A lower starting dose of itraconazole solution is recommended (7.5 mg/kg/day)

*Administration of anti-inflammatory doses of corticosteroids may reduce amphotericin B toxicity and inflammatory response to antigens released from Histoplasma yeast

REFERENCES:

- Selby LA, Becker SV, Hayes HW, Jr. Epidemiologic risk factors associated with canine systemic mycoses. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:133-139.

- Fattal AR, Schwarz J, Straub M. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from lymph nodes of spontaneously infected dogs. Am J Clin Pathol 1961;36:119-124.

- Turner C, Smith CD, Furcolow ML. Frequency of isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis from dogs in Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:137-141.

- Gugnani HC. Histoplasmosis in Africa: a review. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2000;42:271-277.

- Gabal MA, Hassan FK, Siad AA, et al. Study of equine histoplasmosis farciminosi and characterization of Histoplasma farciminosum. Sabouraudia 1983;21:121-127.

- Ameni G. Epidemiology of equine histoplasmosis (epizootic lymphangitis) in carthorses in Ethiopia. Vet J 2006;172:160-165.

- Ameni G, Siyoum F. Study on Histoplasmosis (epizootic lymphangitis) in cart-horses in Ethiopia. J Vet Sci 2002;3:135-140.

- Davies SF, Colbert RL. Concurrent human and canine histoplasmosis from cutting decayed wood. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:252-253.

- Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS, et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:201-209.

- Smith KM, Strom AR, Gilmour MA, et al. Utility of antigen testing for the diagnosis of ocular histoplasmosis in four cats: a case series and literature review. J Feline Med Surg 2017;19:1110-1118.

- Fielder SE, Meinkoth JH, Rizzi TE, et al. Feline histoplasmosis presenting with bone and joint involvement: clinical and diagnostic findings in 25 cats. J Feline Med Surg 2019;21:887-892.

- Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS, et al. Antigen Concentrations as an Indicator of Clinical Remission and Disease Relapse in Cats with Histoplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:1065-1073.

- Renschler J, Albers A, Sinclair-Mackling H, et al. Comparison of Compounded, Generic, and Innovator-Formulated Itraconazole in Dogs and Cats J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018;54:195-200.

- Johnson LR, Fry MM, Anez KL, et al. Histoplasmosis infection in two cats from California. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40:165-169.

- Clothier KA, Villanueva M, Torain A, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in two juvenile raccoons (Procyon lotor) from a nonendemic region of the United States. J Vet Diagn Invest 2014;26:297-301.

- Marx MB, Eastin CE, Turner C, et al. The influence of amphotericin B upon Histoplasma infection in dogs. Arch Environ Health 1970;21:649-655.

- Marx MB, Jones MB, Kimberlin DS, et al. Survey of histoplasmin and blastomycin test reactors among thoroughbred horses in central Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:1701-1705.

- Ackerman N, Cornelius LM, Halliwell WH. Respiratory distress associated with Histoplasma-induced tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1973;163:963-967.

- Reinhart JM, KuKanich KS, Jackson T, et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure.. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:841-848.

- Ludwig HC, Hanzlicek AS, KuKanich KS, et al. Candidate prognostic indicators in cats with histoplasmosis treated with antifungal therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2018;20:985-996.

- Katayama Y, Kuwano A, Yoshihara T. Histoplasmosis in the lung of a race horse with yersiniosis. J Vet Med Sci 2001;63:1229-1231.

- Panciera RJ. Histoplasmic (Histoplasma capsulatum) infection in a horse. The Cornell veterinarian 1969;59:306-312.

- Soliman R, Saad MA, Refai M. Studies on histoplasmosis farciminosii (epizootic lymphangitis) in Egypt. III. Application of a skin test (‘Histofarcin’) in the diagnosis of epizootic lymphangitis in horses. Mykosen 1985;28:457-461.

- Abou-Gabal M, Hassan FK, Al-Siad AA, et al. Study on equine histoplasmosis “epizootic lymphangitis”. Mykosen 1983;26:145-151.

- al-Ani FK. Epizootic lymphangitis in horses: a review of the literature. Rev Sci Tech 1999;18:691-699.

- Blackford J. Superficial and deep mycoses in horses. Vet Clin North Am Large Anim Pract 1984;6:47-58.

- Conti-Diaz IA, Alvarez BJ, Gezuele E, et al. [Intradermal reaction survey with paracoccidioidin and histoplasmin in horses]. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo 1972;14:372-376.

- Cooper VL, Kennedy GA, Kruckenberg SM, et al. Histoplasmosis in a miniature Sicilian burro. J Vet Diagn Invest 1994;6:499-501.

- Goetz TE, Coffman JR. Ulcerative colitis and protein losing enteropathy associated with intestinal salmonellosis and histoplasmosis in a horse. Equine Vet J 1984;16:439-441.

- Hall AD. An equine abortion due to histoplasmosis. Veterinary medicine, small animal clinician : VM, SAC 1979;74:200-201.

- Jones MB, Gonzalez-Ochoa A, Marx MB, et al. Survey of histoplasmin skin test reactions among horses in Mexico. Am J Vet Res 1972;33:1707-1709.

- Rezabek GB, Donahue JM, Giles RC, et al. Histoplasmosis in horses. J Comp Pathol 1993;109:47-55.

- Woolums AR, DeNicola DB, Rhyan JC, et al. Pulmonary histoplasmosis in a llama. J Vet Diagn Invest 1995;7:567-569.

- Burek-Huntington KA, Gill V, Bradway DS. Locally acquired disseminated histoplasmosis in a northern sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) in Alaska, USA. J Wildl Dis 2014;50:389-392.

- Jensen ED, Lipscomb T, Van Bonn B, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in an Atlantic bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). J Zoo Wildl Med 1998;29:456-460.

- Wilson TM, Kierstead M, Long JR. Histoplasmosis in a harp seal. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1974;165:815-817.

- Frame SR, Mehdi NA, Turek JJ. Naturally occurring mucocutaneous histoplasmosis in a rabbit. J Comp Pathol 1989;101:351-354.

- Jensen HE, Bloch B, Henriksen P, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a badger (Meles meles) in Denmark. APMIS 1992;100:586-592.

- Bauder B, Kubber-Heiss A, Steineck T, et al. Granulomatous skin lesions due to histoplasmosis in a badger (Meles meles) in Austria. Med Myc 2000;38:249-253.

- Eisenberg T, Seeger H, Kasuga T, et al. Detection and characterization of Histoplasma capsulatum in a German badger (Meles meles) by ITS sequencing and multilocus sequencing analysis. Med Myc 2013;51:337-344.

- Highland MA, Chaturvedi S, Perez M, et al. Histologic and molecular identification of disseminated Histoplasma capsulatum in a captive brown bear (Ursus arctos). J Vet Diagn Invest 2011;23:764-769.

- Raju NR, Langham RF, Bennett RR. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a Fennec fox. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986;189:1195-1196.

- Weller RE, Dagle GE, Malaga CA, et al. Hypercalcemia and disseminated histoplasmosis in an owl monkey. J Med Primatol 1990;19:675-680.

- Baskin GB. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a SIV-infected rhesus monkey. J Med Primatol 1991;20:251-253.

- Butler TM, Gleiser CA, Bernal JC, et al. Case of disseminated African histoplasmosis in a baboon. J Med Primatol 1988;17:153-161.

- Butler TM, Hubbard GB. An epizootic of histoplasmosis duboisii (African histoplasmosis) in an American baboon colony. Lab Anim Sci 1991;41:407-410.

- Brandao J, Woods S, Fowlkes N, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis (Histoplasma capsulatum) in a pet rabbit: case report and review of the literature. J Vet Diagn Invest 2014;26:158-162.

- Woolf A, Gremillion-Smith C, Sundberg JP, et al. Histoplasmosis in a striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis Schreber) from southern Illinois. J Wildl Dis 1985;21:441-443.

- Farrell RL, Cole CR, Prior JA, et al. Experimental Histoplasmosis, I. Methods for Production of Histoplasmosis in Dogs. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 1953;84:51-54.

- Tewari RP, Campbell CC. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from feathers of chickens inoculated intravenously and subcutaneously with the yeast phase of the organism. Sabouraudia 1965;4:17-22.

- Emmons CW, Rowley DA, Olson BJ, et al. Histoplasmosis; proved occurrence of inapparent infection in dogs, cats and other animals. Am J Hygiene 1955;61:40-44.

- Horwath MC, Fecher RA, Deepe GS, Jr. Histoplasma capsulatum, lung infection and immunity. Future Microbiol 2015;10:967-975.

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis Complicating Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Blocker Therapy: A Retrospective Analysis of 98 Cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:409-417.

- Hage CA, Bowyer S, Tarvin SE, et al. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:85-92.

- Rowley DA, Haberman RT, Emmons CW. Histoplasmosis: pathologic studies of fifty cats and fifty dogs from Loudoun County, Virginia. J Infect Dis 1954;95:98-108.

- Turner C, Smith CD, Furcolow ML. The efficiency of serologic and cultural methods in the detection of infection with Histoplasma and Blastomyces in mongrel dogs. Sabouraudia 1972;10:1-5.

- Smith CD, Furcolow ML, Hulker P. Effect of immunosuppressants on dogs exposed two and one-half years previously to Blastomyces dermatitidis. Am J Epidemiol 1976;104:299-305.

- Greer DL, McMurray DN. Pathogenesis of experimental histoplasmosis in the bat, Artibeus lituratus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1981;30:653-659.

- Tesh RB, Schneidau JD, Jr. Experimental infection of North American insectivorous bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) with Histoplasma capsulatum. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1966;15:544-550.

- Hasenclever HF, Shacklette MH, Hunter AW, et al. The use of cultural and histologic methods for the detection of Histoplasma capsulatum in bats: absence of a cellular response. Am J Epidemiol 1969;90:77-83.

- Taylor ML, Chavez-Tapia CB, Vargas-Yanez R, et al. Environmental conditions favoring bat infection with Histoplasma capsulatum in Mexican shelters. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;61:914-919.

- Klite PD, Diercks FH. Histoplasma Capsulatum in Fecal Contents and Organs of Bats in the Canal Zone. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1965;14:433-439.

- Cole CR, Farrell RL, Chamberlain DM, et al. Histoplasmosis in animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1953;122:471-473.

- Rowley DA. Pathological studies of histoplasmosis; preliminary report on fifty cats and fifty dogs from Loudoun County, Virginia. Public health monograph 1956;39:268-271.

- Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in cats: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987;190:1445-1448.

- Davies C, Troy GC. Deep mycotic infections in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1996;32:380-391.

- Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:182-187.

- Schulman RL, McKiernan BC, Schaeffer DJ. Use of corticosteroids for treating dogs with airway obstruction secondary to hilar lymphadenopathy caused by chronic histoplasmosis: 16 cases (1979-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;214:1345-1348.

- Clinkenbeard KD, Cowell RL, Tyler RD. Disseminated histoplasmosis in dogs: 12 cases (1981-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;193:1443-1447.

- Lau RE, Kim SN, Pirozok RP. Histoplasma capsulatum infection in a metatarsal of a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1978;172:1414-1416.

- Saunders JR, Matthiesen RJ, Kaplan W. Abortion due to histoplasmosis in a mare. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983;183:1097-1099.

- Hodges RD, Legendre AM, Adams LG, et al. Itraconazole for the treatment of histoplasmosis in cats.. J Vet Intern Med 1994;8:409-413.

- Liang KV, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis with tenosynovitis of the hand and hypercalcemia mimicking sarcoidosis. J Clin Rheumatol 2004;10:138-142.

- Balows A, Ausherman RJ, Hopper JM. Practical diagnosis and therapy of canine histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1966;148:678-684.

- Cook AK, Cunningham LY, Cowell AK, et al. Clinical evaluation of urine Histoplasma capsulatum antigen measurement in cats with suspected disseminated histoplasmosis. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:512-515.

- Cunningham L, Cook A, Hanzlicek A, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of Histoplasma Antigen Detection by Enzyme Immunoassay.y. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2015;51:306-310.

- Rothenburg L, Hanzlicek AS, Payton ME. A monoclonal antibody-based urine Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (IMMY(R)) for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2019;33:603-610.

- Jarchow A, Hanzlicek A. Antigenemia without antigenuria in a cat with histoplasmosis. JFMS Open Rep 2015;1:2055116915618422.

- Spector D, Legendre AM, Wheat J, et al. Antigen and antibody testing for the diagnosis of blastomycosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:839-843.

- Richer SM, Smedema ML, Durkin MM, et al. Development of a highly sensitive and specific blastomycosis antibody enzyme immunoassay using Blastomyces dermatitidis surface protein BAD-1. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014;21:143-146.

- Mitchell M, Stark DR. Disseminated canine histoplasmosis: a clinical survey of 24 cases in Texas. Can Vet J 1980;21:95-100.

- Pratt CL, Sellon RK, Spencer ES, et al. Systemic mycosis in three dogs from nonendemic regions. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012;48:411-416.

- Reginato A, Giannuzzi P, Ricciardi M, et al. Extradural spinal cord lesion in a dog: first case study of canine neurological histoplasmosis in Italy. Vet Microbiol 2014;170:451-455.

- Reyes-Montes MR, Rodriguez-Arellanes G, Perez-Torres A, et al. Identification of the source of histoplasmosis infection in two captive maras (Dolichotis patagonum) from the same colony by using molecular and immunologic assays. Rev Argent Microbiol 2009;41:102-104.

- Sano A, Ueda Y, Inomata T, et al. [Two cases of canine histoplasmosis in Japan]. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 2001;42:229-235.

- Ueda Y, Sano A, Tamura M, et al. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis by detection of the internal transcribed spacer region of fungal rRNA gene from a paraffin-embedded skin sample from a dog in Japan. Vet Microbiol 2003;94:219-224.

- Schumacher LL, Love BC, Ferrell M, et al. Canine intestinal histoplasmosis containing hyphal forms. J Vet Diagn Invest 2013;25:304-307.

- Sykes JE and Toboada J. Histoplasmosis. in Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. Sykes JE Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2019.

- Hage CA, Kirsch EJ, Stump TE, et al. Histoplasma antigen clearance during treatment of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS determined by a quantitative antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011;18:661-666.

- Plumb D. Amphotericin B. in Veterinary Drug Handbook. 9th ed. Stockholm, WI: Pharma Vet Inc.; 2018.

- Legendre AM, Rohrbach BW, Toal RL, et al. Treatment of blastomycosis with itraconazole in 112 dogs.. J Vet Intern Med 1996;10:365-371.

- Mawby DI, Whittemore JC, Fowler LE, et al. Comparison of absorption characteristics of oral reference and compounded itraconazole formulations in healthy cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:195-200.

- Wheat J, Hafner R, Korzun AH, et al. Itraconazole treatment of disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS Clinical Trial Group. Am J Med 1995;98:336-342.

- Mawby DI, Whittemore JC, Genger S, et al. Bioequivalence of orally administered generic, compounded, and innovator-formulated itraconazole in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:72-77.

- Mazepa AS, Trepanier LA, Foy DS. Retrospective comparison of the efficacy of fluconazole or itraconazole for the treatment of systemic blastomycosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:440-445.

- Lestner JM, Roberts SA, Moore CB, et al. Toxicodynamics of itraconazole: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:928-930.

- Legendre AM. Blastomycosis. in Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat.. Greene C. Ed. Fourth ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012.

- Wheat LJ, Connolly P, Smedema M, et al. Activity of newer triazoles against Histoplasma capsulatum from patients with AIDS who failed fluconazole.. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;57:1235-1239.

- Wheat LJ, Connolly P, Smedema M, et al. Emergence of resistance to fluconazole as a cause of failure during treatment of histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency disease syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:1910-1913.

- Kabli S, Koschmann JR, Robertstad GW, et al. Endemic canine and feline histoplasmosis in El Paso, Texas. J Med Vet Mycol 1986;24:41-50.

- Restrepo A, Tobon A, Clark B, et al. Salvage treatment of histoplasmosis with posaconazole. J Infect 2007;54:319-327.

- Freifeld A, Proia L, Andes D, et al. Voriconazole use for endemic fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:1648-1651.

- Thompson GR, 3rd, Rendon A, Ribeiro Dos Santos R, et al. Isavuconazole Treatment of Cryptococcosis and Dimorphic Mycoses. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:356-362.

- Freifeld A, Arnold S, Ooi W, et al. Relationship of blood level and susceptibility in voriconazole treatment of histoplasmosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:2656-2657.

- Vishkautsan P, Papich MG, Thompson GR, 3rd, et al. Pharmacokinetics of voriconazole after intravenous and oral administration to healthy cats. Am J Vet Res 2016;77:931-939.

- Sakai MR, May ER, Imerman PM, et al. Terbinafine pharmacokinetics after single dose oral administration in the dog. Vet Derm 2011;22:528-534.

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:807-825.